A grub is chosen for a higher purpose.

guest story by Zyzzyva

tags: body horror, nsfw

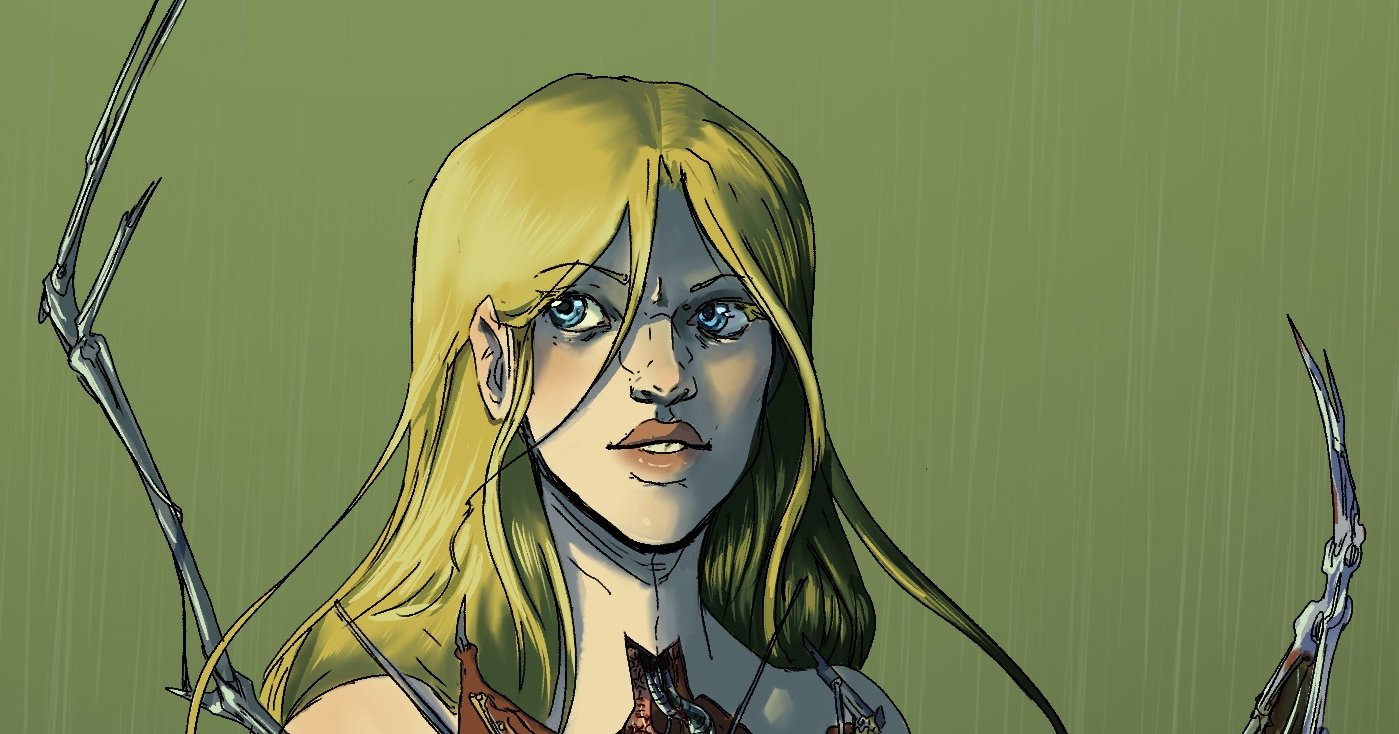

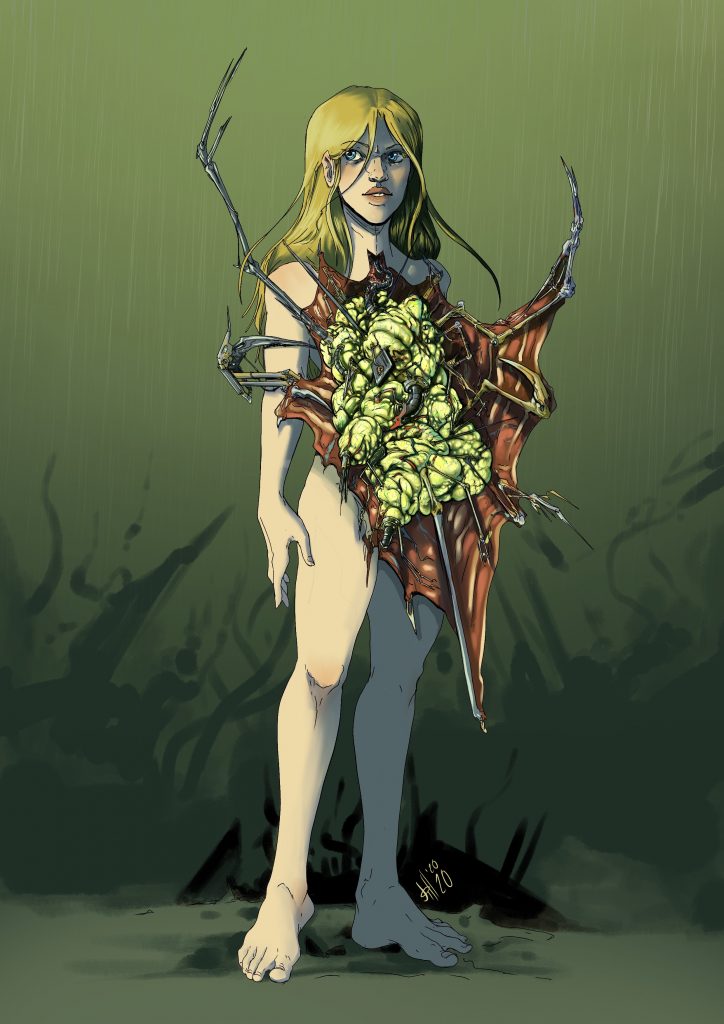

art by Jill

The hierophant Tseqaq’s rearmost ventral wombtank was a fat, squat cylinder of glass riveted into the flesh of the great Scyrrhian. One of hisher breeding glands squirted hot grimy fluid into the watery medium of the wombtank and it came to life, filled with uncounted millions of herhis microscopic spawn. For a long time that was all there was to see: the tiny creatures ate, and grew, and fought, and eventually began to feed on each other. The liquid clarified as its resources were exhausted and its population grew and solidified. By the time they were visible to the naked eye there were only a few thousand grubs left, each a cannibal of millions of its siblings.

Their fathermother did not notice, nor would shehe have cared if heshe did; this was how Scyrrhians grew. One of herhis secondary slavecortexes managed the rearmost ventral wombtank, and periodically dipped thermometers and agitator rods and tongues in and out of the liquid to ensure its minimal habitability. Once a grub, blind and hungry, found a sensory probe being inserted and opportunistically tried to digest it; a tiny sliver of amusement was permitted to filter up to Tseqaq’s central personalityself. Beyond that none of the hierophant’s vast intelligence spared a thought to hisher childrenspawn.

One hundred and twenty-three million engineheart beats and nineteen thousand engineheart refueling cycles after Tseqaq’s filthy seed first drooled into the wombtank, the slavecortex found the grubs adequate. There were about a dozen left, the fastest and smartest and hungriest of them all, each a pale translucent mass the size of a thigh packed with haphazardly improvised organs. The bottom of the wombtank irised open, spilling steaming hot water and panicked, squirming grubs onto the corroded metal gratings below. The water drained quickly, to be recycled into the hierophant’s thirsty systems; the grubs thrashed and keened piteously under the naked gaze of their motherfather for the first time.

One of the grubs was a little larger than the others; the secondary slavecortex picked it out quickly and a pseudopod, grafted with metal into a grasper, closed around it and lifted it from the grating. Scratched lenses and cloudy eyes peered at it, approved, and passed the grub up into a peristaltic valve to the outside, to be considered by the slavecortex’s masterself.

The air of Scyrrh was caustic and cold. The grub’s raw wet skin burned and blistered. On its own it could in a while survive, harden, adapt to the environment it found itself in; but now it was being brought before its fathermother’s personalityself and there was no time. More graspers, external, larger, stronger, passed it over the mountain of oily flesh and rusty metal that composed Tseqaq.

The grub, twitching with what it was still too young to understand as pain and fear, came before herhis face. Meat and machinery peered at it, listened to it, tasted it. A pulse of thought traveled backwards and down through hisher body: the latest litter of childrenspawn were acceptable.

Another, marginally more favoured slavecortex took possession of the surviving grubs and began the program of grafts and enhancements that would prepare them for their new existence as engineerparasites of the hierophant’s body. The firstborn grub’s biomass was quickly recycled into herhis systems; but its tiny spark of a soul was fed to a different, deeper hunger, and Tseqaq savoured its consumption for a long, long time.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

The engineerparasite that had once been the third-largest grub of its litter was smart, and strong, and above all lucky; it grew and prospered on the hierophant.

It was a lanky metal spider now, a metre or two across; it roamed over and through its fathermother’s body on six mostly matching metal legs, doubling as hands and as weapons. Where they met at its centre its fleshself, which had once been the whole of the grub, pulsed and quivered. Like all the engineerparasites, it had quickly given its maw teeth and crushing metal mandibles; more unusually, a fortunate bit of salvage had let it encase most of its fleshself in glass, so that it hung like a fishbowl from its own underside. Underneath the glass it had taken further advantage by packing in vulnerable eyes and delicate cameras. It had some of the best vision of any engineerparasite on the hierophant, and more and more frequently it found itself not fleeing from siblingpredators but hunting them as siblingprey.

Most of its existence, though, was work. Its motherfather’s enormity required constant effort to maintain, and hisher childrenspawn were kept busy continuously doing so. It oiled metal, moistened organs, and soothed the raw seams where the two met. It helped construct new machinery and clear space for the growth of new limbs, and ripped apart broken iron and meat with equal vigour. It killed the occasional trueparasite from outside that found and tried to settle on its parenthost. But its lovehate for herhim was ambiguous; heshe provided a modicum of material to enhance itself with, and the fuelteats that were the only consistently reliable source of nourishment for an engineerparasite, and above that a purpose that ordered its existence. It still lived in fear of the hierophant’s eternal hunger, which frequently had it scuttling into hiding and hoping shehe would pluck a different childspawn off himherself to be devoured. When one of Tseqaq’s major organs stroked and had to be destroyed before gangrene set in, and all the engineerparasites swarmed it as one in a feeding frenzy of jagged metal and sharpened bone, it was with a real sense of vengeful joy that it ripped through its motherfather’s body. Nor was it alone in feeling this way.

But that was simply existence as an engineerparasite; it was not Tseqaq’s peer and it hardly considered that it could ever be so. Heshe did have peers; shehe was too large to killed by

any outside force, and so were others, and these great Scyrrhians met occasionally, by chance or arrangement, as theythey roamed the fecund foulness of Scyrrh’s surface. Theythey would come alongside each other, and tendrils of flesh and mesh-wrapped copper cable would lash out and grip the other, and the vast mistressmasters of Scyrrh would squirm against each other like grubs bumping blindly in a wombtank, and theythey would speakfuck. Glands and orifices would gape, hot and foul fluids—tar-black and gritty, pus-white and creamy, and every variation in between—would spill and ooze; genetic material and design schematics would be passed back and forth; and at the peak, the titanic wills and vast intellects of the central personalityself of hierophant Tseqaq and that of hisher interlocutor would commune.

As this went on the engineerparasites would hide and brace themselves from the eathquake shaking and crushing that the speakfucking was to a being their size. The whole side of their parenthost would be bruised and crumpled when theythey were done, and it would take whole engineheart refueling cycles to repair herhim. Worse than that, an incautious engineerparasite might be knocked by the violence onto the other great Scyrrhian, a guarantee of being consumed like an especially novel delicacy by himher once discovered, and being found wouldn’t take long; or, worst of all, might be thrown from the two of themthem entirely. Growing on its own in the waste of bile and rust that constituted the surface of Scyrrh was the only real way for an engineerparasite to become its own individual, to flourish into an independent being; but it was so much more likely that, confused and disoriented, it would just be eaten by some other midsized independent Scyrrhian long before that point.

The engineerparasite was not satisfied with its lot. The hunger to consume, to evolve, to grow, that drove the hierophant was smaller but no less urgent in it. But its niche was sufficient. No Scyrrhian ever grew fast enough to slake its fires; but it was still growing and evolving quickly. Its limbs were long and supple; its eyes were manifold and sharp. Its fleshself was fat and well-protected. If it could keep away from its motherfather’s attention, it would do fine.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

It came to Tseqaq’s attention in the following way.

The hierophant had met the ecclesiarch Dveiq and was even now speakfucking himher. The engineerparasite had happily been well inside its parenthost when the first appalling collision occurred, and had wasted no time in burrowing itself into an abscess of one of herhis secondary intestinal tracts that it had noted earlier and stored away for just such an occasion. Secreted there, it was well-braced to endure, and also dig its sharpest cutting tools into the sore flesh just a little as it waited.

Outside and above and around it, the two great Scyrrhians were communing intently indeed. Plans far older than the engineerparasite were being discussed, and indeed coming toward fruition; the two spoke long and fucked hard. As it ended, and as the engineerparasites on both began to untense in relief at survival, one of Dveiq’s sphincters dribbled a spherical metal cage to Tseqaq, which took it inside himherself.

The engineerparasite had, unbeknownst to itself, bedded down near a tertiary slavecortex; a bundle of nerves even smaller than its own mind, but just aware enough to be irritated by the engineerparasite’s spiteful little attack on the intestine. When the slavecortex’s masterself pulsed down a need for a clever and adaptive childspawn for herhis plans, it was a matter of

no time at all for a quasithought pointing out the engineerparasite to flicker back up. Tseqaq’s personalityself considered the numerous candidates hisher distributed subminds had proposed, and agreed on that specific engineerparasite. It had barely extracted itself from the abscess again and set out for the damaged gearing it had been mending, when a wave of phlegm flushed through the cavity and shehe coughed it up into a waiting claw.

It thrashed desperately, but the claw was the size of the entire engineerparasite, its metal reinforced and well-bolted, its flesh hard and calloused. The engineerparasite could not harm

it meaningfully before it went into its fathermother’s digestive abattoir. It stabbed out wildly anyways, and was surprised when, rather than being devoured, it was tossed ungently into a small chamber, with no alkali chemical baths or grinding toothmills at all.

It was almost alone in there; there was also a metal cage there, a little broader than its full legspan. Inside were two creatures, and it hesitated for a moment in confusion. They were flesh, through and through; highly organized bone and muscle and sense organs, without even the simplest grafted claws or engines. With them was some sort of frame, shaped a little like the two of them, but metal and hollow and ripped open at the widest point.

It was so startled by the presence of the two creatures—their damaged outer skin, their weirdly distinguished movement and manipulation and sensory limbs—that it missed its short window to try to escape its parenthost. Smaller internal tentacles grabbed it, immobilizing it again; and then ripped its legs off. The engineerparasite—now hardly more than a grub again, a fleshself with a few extra bits and some jagged broken joints where it had used to have mobility—was in agony, and confusion, and agony. What was its motherfather doing?

Noises came from the cage.

More delicate limbs still unfolded from the walls and began cleaning the ragged edges of the grub: carefully pulling out the legstumps and suturing the wounds, removing loose sensors and drilling clear the neural jacks beneath them, peeling off its precious glass shield. A shovel picked it up, naked and alone, and carried it carefully to the cage. The creatures made more noises and moved away. Two claws peeled an entrance open—the grub was moved in—and then, before it could even figure out what was happening, it was jammed into the central cavity of the frame.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

She awoke, which surprised her because she had never awoken before; and stranger still she could feel the memories of a lifetime’s worth of awakenings down below that.

She wasn’t breathing. She had never breathed, needed to breathe; she looked down in confusion and saw her chest splayed open, a mass of claws and needles and tools splayed out like the smashed ribcage she didn’t possess; and inside, almost filling her torso, her fleshself.

The world spun around her. That was her fleshself, yes; it had once lain at the centre of her glorious spidery body, and now she was looking down at it from the eyes topmost on her new frame. That was her. The breathing was someone else, someone who wasn’t her, or at least hadn’t been.

She concentrated on the ribs, and flexed them. They folded up neatly, packing machinery and equipment tightly into the cavity with her fleshself; then the outer pieces fit themselves together, their outer layers designed to mimic a seamless spread of flesh. She stroked it with one manipulator (“fingertip”, the word came to her unexpectedly) and it was soft and smooth. Her fleshself underneath was crowded but not quite unpleasantly so; and seeing her torso neat and whole (again) was relieving in an unexpected way.

She looked up again, trying to take in her surroundings better. She was (still) in the cage she had been slid into (that she had been held prisoner in), but the latter half of the thought was not her and tagged with pain in ways she didn’t quite want to examine yet. Xantcha, the creature she had first seen a moment ago (her former self (but not)), lay slumped on the floor of the cage. The woman’s head had been demolished, blood and brains and thought and memory dripping out of a dozen rents, and she felt uncomfortable examining the dead body of someone else (who was her (sort of not really)).

The other (Gerven) was in the corner, trembling and almost frozen (with horror). She took a step towards him, memories of bipedal locomotion surfacing easily but ideas of what to do or say much harder to find. She stopped and hesitated. She was not Xantcha; she was a Scyrrhian grub wearing a body that had been carefully engineered to look like them (like a human (yes, human, that was it)). His—something, she somehow didn’t want to look into that—his co-prisoner Xantcha had been dismantled to provide her with aptitude with human bodies and human culture. That was not a position to introduce yourself from.

The concern became academic a moment later when a needle-tipped metal limb snaked through the bars of the cell and stabbed through the back of his skull. The front of his face distorted with pressure from behind in a way she knew was not survivable; red fluid (blood) dribbled from orifices (his eyes, ears, nose, mouth). His body sat there for a moment on the floor, and then stood up; or, rather, was lifted by the back of the head. His limbs and face dangled slack alike; his bloody jaw opened, and he spoke.

“I have a new purpose for you, progenyslave,” said heirophant Tseqaq.

Author’s Note: This one is based, pretty obviously, off Magic the Gathering’s Phyrexians. Despite the name of one of the human characters, though, the protagonist isn’t cribbing from Xantcha from Urza’s Saga so much as Belbe from Nemesis. The whole thing, arguably, is inspired by my disappointment at discovering that Phyrexian “newts” are actually the native humanoids of the plane, and not slimy skinless amphibians. I fixed that, for damn sure!

The actual plot of this was originally rather more complex, with the main character actually going on a spy mission intercut with its backstory, but in the end the backstory was so much stronger and more interesting that I just stuck with that. Makes the title a wee bit vestigial, but now the reader can imagine their own adventures to taste!

And it’s not like Scyrrhans aren’t all up on the vestigial parts anyways. 😉

The art is courtesy of the amazing Jill, who is also on Twitter and Patreon. She absolutely nailed the balance between weird, attractive, horrifying, and <vomit emoji> that I wanted for this piece, just perfectly.