An early-medieval warrior learns some unexpected things about her queen, and gets some unexpected rewards.

guest story by zyzzyva

tags: historical fiction, transformation

MILES THEODELINDA strode confidently into the palace, her helm under one arm, her spear and shield slung over her back, her hauberk cleaned and gleaming in the morning sun. Her retainers Luitprand and Radelchis came behind her, and behind them, a pair of servants with a heavy iron-bound chest: the plunder from the summer’s campaign. It had been a good season. Three Friulian forts taken, with treasure and hostages; and their chief Hotimir had agreed, at the end of the summer, to the payment to the Queen of tribute in perpetuity. It was anyone’s guess whether he’d still be paying it a year hence; Theodelinda had no doubt whatsoever that he wouldn’t be paying it the year after that. But she had the forts, and their loot, and the first year’s payment, and she was about to be well rewarded for her service.

In through the great gates, past the chapel, up the bank of stairs to the aula, the royal audience hall. Theodelinda, tall, fit, and not lugging fifty pounds of silver, waited at the top for the others to catch up. She intended to walk out of this audience with a shiny new benefice, and if that meant choreographing her entrance for maximum effect, she would do so. She adjusted her hauberk again, and nodded to Luitprand and Radelchis, who shoved the aula doors open. She walked in as boldly as she dared, and strode down the long hall towards the throne.

“Miles Theodelinda,” proclaimed one of the guards at the door, as she passed him. There was motion at the far end, as the Queen and her councillors turned to look at her. Theodelinda could feel herself start to sweat a little, under her armour. Why was the hall so damn long — well, for exactly this reason, of course. She knew she wasn’t interrupting, was in fact expected at this hour, but she was still off-balance. She clenched her jaw, hoping she was still too far away for that to be noticed, and glanced around the throne. The clerk Hraban — he’d always been a help to her career, it was good that he was here. Comes Grimoald — not so good. He was a real fucker, honestly. But mostly allies, or at least indifferent careerists from other parts of the kingdom. That was a good sign, she hoped.

“Your grace!” Theodelinda declared, once she was comfortably close to the throne. She dropped to one knee and lowered her head. “The fruits of conquest from Friuli!” She gestured behind her with one hand, silently praying. She hadn’t dared glance behind her the entire walk up the hall, and had no idea if the servants had kept up well enough for this to work, properly dramatically, but then there was the thud of the chest hitting the floor and tipping forward, just like they’d practiced, and the chiming rush of silver, coined and barred, spilling out over the floor. A worn old Gothic penny rolled past her line of sight. She stifled her smile.

There was a polite spattering of applause from the court, probably more for the theatre of the business than anything else. Which was the point, of course. They liked this sort of thing, and so Theodelinda had to be good at it too. But there was really only one person that she had to impress.

“You may rise,” said the Queen, her voice ringing in the hall. Theodelinda did, smiling. The Queen sounded pleased and when Theodelinda finally met her eyes she saw that she was smiling too.

The Queen sat on her throne, somehow casual and unconcerned even in the air of dignity and ritual that permeated the palace. She was magnificently dressed, far beyond anyone else in the aula. Others, more regularly present at court than her, had spoken to Theodelinda of her beauty: she could see their point, even if she had never really felt the appeal, herself. Here and now, all of it was just another aspect of her authority, powerfully right and proper. And the Queen was pleased with Theodelinda. She carefully avoided turning from the Queen to glance over at Grimoald. She could imagine his scowl and it was almost as good as the Queen’s smile.

“I have had my eye on you for some time,” said the Queen, and Theodelinda stifled a wider smile. “Your service to the kingdom and to me has been without compare.”

“Your grace is too kind,” murmured Theodelinda.

“Nonsense,” said the Queen. “You have returned here victorious, with the spoils of — ?”

“The fortresses of Palme, Chedad, and Sacil.” Actually, they were little more than wooden-walled camps — the Friulians having little in the way of permanent settlements, and less in the way of forts — but she’d memorized their names to sound impressive for just this occasion. “And an annual tribute from their great chief.” That got an appreciative murmur around her.

“That is, miles, an excellent service. One well worthy of reward.” The talking died down again. “Come forward and kneel, my good and faithful servant.”

Theodelinda moved forward, a fierce joy burning inside her. She managed a quick glance over to Grimoald, whose jaw was tight but face was impassive. Well, maybe it was too much to hope for that he would humiliate himself with overt displeasure in front of the Queen. She reached the very foot of the throne and knelt.

“I can’t imagine that that chief of theirs will pay tribute for long,” said the Queen, thoughtfully. Theodelinda thought the same, but wasn’t sure where this was going. “All the more reason to have a talented warrior there to keep them in line. A marcher lord, maybe.” Theodelinda started rolling the words ‘Margrave of Friuli’ around in her head and couldn’t stop.

The Queen extended one slender hand down to her. Theodelinda clasped it between her own. The Queen nodded and she let the words spill out. “I do swear here, on my faith and before my peers, that I will do true service to you my Queen and defend her faithfully from all enemies.”

“Stand, marchio Theodelinda.”

She rose, glowing with pride.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

THE MESSENGER arrived in the middle of the night; Theodelinda was woken with the beginnings of a hangover pulsing in her temples. It had been a busy evening. Dinner with the Queen — Theodelinda had been third on her right, behind only dux Athaulf and dux Gundiperga — and she’d been toasted and praised, and a half-dozen ambitious young milites had come sniffing around for a place on her new margravial retinue. Radelchis had picked a fight with a retainer of Grimoald’s and hit her over the head with a pitcher. Then back to her residence to drink more and speak more openly with Luitprand and Radelchis about their ambitions. This house in Pavia, for starters: it was more than big enough for her needs before, but she had a much improved place in the world now, and needed more room for entertainment and simply for display. They’d been too drunk to decide whether she should try and build a new house somewhere in town, or just buy the ones next door and punch out the interior walls.

Now she was awake again, and sleepily cranky, and confused. The girl had insisted that the Queen needed her presence back at the palace, which made no sense — all of the ceremonies and drinking had happened yesterday, and anything else could wait until morning. Honestly, the only explanation she could think of was that this was some hastily-planned trap of Grimoald’s, though surely he couldn’t be stupid enough to try to assassinate her on the streets of Pavia the very night after the Queen had granted her Friuli. Besides, the girl had been serving the Queen at dinner, and had a sealed lump of wax the size of her fist to validate her, so Theodelinda ultimately decided just to bring her sword and trust in her strong right arm if this turned out to not be on the up-and-up.

No one interrupted them. The messenger led her through the town confidently, despite carrying nothing but a small lantern. Even if Theodelinda hadn’t been on edge, watching at every corner for thugs in Grimoald’s pay to jump her, she would probably have been less cavalier about walking the streets of Pavia unaccompanied in the middle of the night. She kept her hand on her sword the whole way. But the few other passers-by they saw by the tiny light of the lantern kept well out of their way.

They arrived at the palace from the side, and the girl led her in a small postern gate. There was no guard, the messenger instead unlocking and locking it with an iron key. Then in through the halls of the palace. Theodelinda was unfamiliar with this part, although she hoped her new title would be changing that soon. She was, she thought, heading somewhere towards the Queen’s private chambers, which was exciting even if she still had no idea what was going on.

She was right about the location: the girl eventually led her into a private reception hall somewhere deep in the palace. It was empty except for her and the Queen, lounging comfortably on a chair across from her.

“You may stay if you wish, Ansa,” said the Queen. Well, the messenger was here too. Theodelinda was even more confused — she couldn’t think of anything that would require her and the Queen alone in the palace in the dark of night, and even less that would involve the presence of some random servant girl.

“Thank you, your grace,” said the girl — Ansa. “I do love this part.”

“I know,” said the Queen, indulgently. “Now. Marchio Theodelinda. Do you know why I have summoned you?”

She had no idea. “I have no idea, your grace.”

The Queen chuckled. “I didn’t imagine you did. I wasn’t just being kind when I said I’ve had my eye on you. You’ve done well for yourself out east.” Theodelinda flushed but still wasn’t sure what was happening. The Margraviate had been more than she could have reasonably hoped for: if the Queen was going to bestow some other favour on her, she wouldn’t argue, but she couldn’t understand why the Queen would. “Do you remember comes Theudoald?”

Theodelinda did, but the question was so unexpected it took a moment for her mind to catch up. “Yes, he was Count of, uh, Nursia. Died in battle against the Exarchate this past summer.” He had a reputation as a monster of a fighter, but entirely in the south; Theodelinda had seen him only twice, at court in Pavia, from a distance. She’d never spoken a word to him, or even his retainers.

“A great loss. He was the mightiest warrior in the Kingdom.”

Theodelinda made the connection. “Your grace flatters me beyond reason. I could never compare to —”

The Queen waved a hand. “Strength of arms is a talent, and talents can be granted no less than titles.” Theodelinda blinked. “He had other traits. Ambitious, but loyal. Generous to his lessers, magnanimous to his foes. He wore his power well. That is what I saw in you.”

Theodelinda stood, slackjawed. “Your grace is… very perceptive,” she stumbled, trying desperately to guess what was going on. Ansa was giggling off to the side somewhere. After that whole little speech about charity, she couldn’t haul off and punch the servant, but her confusion was boiling into frustration that she was being made the butt of a joke she couldn’t see. Ansa was the Queen’s mistress, maybe? Maybe that was what she was missing?

“Comes Theudoald was my palatinus. A loyal servant above and beyond the men and women out in the palace. So is palatina Ansa, in a different capacity. There are a few more. A half-dozen, maybe. I would have liked you and Theudoald to be fighters for me together, but he is dead now and I have no palatinus champion. I am offering you a title you cannot speak of except to me, with no reward except for the pleasure you bring me and the strength I will gift you. But Theudoald gloried in it, and I know you would too.”

Her head seemed to be spinning. Theodelinda would gladly accept a commission from the Queen, even a secret one, but — “gifting strength”? “Talents granted no less than titles”? What was happening?

“There is one more thing,” said the Queen, with a smile. “You will understand what I am offering when you understand what I am. SEE.”

Everything in the room was just as it had been. Everything in the room was wrong.

The Queen spilled over Her chair, far too large for its merely human frame. She filled the whole end of the room. Her bulk, armoured and spiny and thick and chitinous and fleshy and everywhere squirming with obscene vitality, filled yards of space; Her longest limbs — and She had dozens, of every shape and configuration — sprawled for yards further. The nearest, a long black multi-jointed clawed arachnoid leg, scraped blindly at at the stone of the floor only inches from Theodelinda’s feet. The Queen was everywhere in motion, Her limbs scratching and stroking and caressing and clawing at each other, at Her great fleshy centre, at the torn and ravaged walls of the room; Her body was covered in eyes and mouths and genitalia, great and small, human and animal and insect and stranger still; great fields of spines rising and falling like waves, scales gleaming, orifices drooling ichor or steaming with breath.

The worst of it was Her face, the Queen’s plain, human face, unaltered and unaffected, smiling gently at Theodelinda from out of the obscene mass of Her flesh.

No. The worst of it was the sudden understanding, striking Theodelinda with the force and certainty than it never had before, that the Queen was the most beautiful woman she had ever seen.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

THEODELINDA awoke in her room, feeling surprisingly rested. She had come home from the dinner at the palace, drank and talked with Luitprand and Radelchis, and only then gone to bed. A late night, like she’d had many times before, but she felt like she’d slept for a week.

At the table for breakfast they talked again, more subdued (or at least more sober). The Queen was holding court in the most literal sense today, in the great yard before the palace. It was Theodelinda’s right, and duty, to attend, and assist in passing judgment in the assembly. She had been before, of course, but she was not just a freewoman of the assembly, now, she was an officeholding noble. Her retainers were not just there as freemen themselves, they were hers, now, and they spent a little while together planning out how and where they would stand. Theodelinda had not had time to buy new clothes appropriate for a marchio, yet: it had not even been a day, and she’d spent most of that feasting and drinking and sleeping and — sleeping. Still, she wanted to cut her best figure at the assembly. Her bright green tunic, with a little gold thread around the neck; her good blue pants and good leather boots; two gold(-leaf) bracelets; and of course her belt, half a hand wide and buckled with bronze. She’d be able to afford a better belt soon, a belt really fit for a marchio. It was an exciting thought.

At noon, as the yard filled, Theodelinda and her men were up at the front right — about proportionally where she’d sat at the banquet last night. Older and more prestigious royal officers and their retinues filtered in around her, and to her relief she didn’t feel too out of place. She wasn’t even the least well-dressed at this end of the stands. But far from the best. Comes Grimoald was across the field from her, more or less, and with a great deal more gold on his clothes and neck and wrists. And his belt was a full handspan, with a golden buckle.

At just about the moment the stands were full — she always had a good sense of timing — the Queen entered. There was a hush of voices and the quieter creak of people straining on tiptoes to see. For the free citizenry of Pavia, down at the far end of the stands, this was probably the closest they would get to the Queen. It was the closest Theodelinda had been, until her arrival at the aula yesterday.

The Queen did not disappoint. Beautifully attired as always, clad in fur and chitin and glistening mucus, she crawled out of the palace gate, her claws tearing up great clods of earth from beneath her as she moved. She proceeded to the heavy oak throne at the head of the assembly, wriggled herself over the back of the chair, enfolding it in her great massy body, and settled down onto it. The assembly seated themselves, too, and then there was stillness, except for the ceaseless squirming of the Queen’s flesh.

Theodelinda squeezed her eyes shut and opened them again. Something was different. This was not the way it had been at the last assembly she had attended, in the spring. She — was not seated at the back this time. She was close enough to see the expression on the Queen’s face as it extended out on a mighty coil of flesh to speak. That was probably what it was, her literal moving-up-in-the-world. She had best get used to it. She intended to remain a royal beneficiary for a long, long time.

“Langobardi Romanique!” called the Queen, loudly. “You are assembled today in council to see justice done. Will you swear on your faith and your honour to give true verdicts by the evidence and the law?”

“We swear,” chorused Theodelinda, along with the rest of the assembly. The first ritual affirmation of the day.

And the last for quite a while, because the first case very quickly bogged down into a sea of witnesses and counterwitnesses, oaths and denials, scholars batting obscure glosses of the Code of Luitprand back and forth at each other. It was some business from down south: dux Gundiperga and marchio Rosamunda fighting over a piece of land that might or might not have been gifted to a monastery owned by Gundiperga’s family. It was probably a very valuable property (Theodelinda hoped it had better be valuable, as the argument entered its second hour), but it really had no relevance to her.

But that wasn’t really true anymore, she thought, and sat up with a start quick enough to startle Radelchis on her right. She wasn’t an ambitious young miles scrabbling her way up in the world anymore, with no more concerns in Pavia than the narrow bounds of her own home County and raiding the Friulians. She was a marchio, a figure in the affairs of the kingdom (even if her Margraviate was wedged between her old home County and the Friulians). This case wasn’t about the law, or even really the land at stake; it was politicking by other means, Gundiperga and Rosamunda flexing their muscles at court. Theodelinda could be of aid to either of them, and they could be of aid back. She glanced across at Grimoald, who was watching with attention (if, more than an hour in, no longer alertness). He had an opinion on this. She needed to come up with one of her own, soon.

But — fortunately, perhaps, for the other petitioners, and most of the assembly — the Queen didn’t seem to have much of an opinion of her own. After two hours of argument churning the facts and the law to featureless mud, the Queen abruptly put the matter to rest with an order that a legal clerk of hers travel south and come up with an impartial brief for the next assembly. The two women down on the field before the Queen accepted this delay with apparent grace; the assembly ratified it with a shout and considerable relief. Theodelinda was relieved, a little, too — she had time to figure out what was actually at stake in this case. By the time Johannes returned with his brief, she promised herself, she would be able to tell whether the ultimate verdict was good or bad for her.

The next few were simpler, and less freighted. Unranked milites, and free of every grade down to tenant farmers, mostly with their own lesser squabbles over land. Without political connections tugging each case every which way, the Queen and her clerks could knock them off quickly and with justice. A fratricide (wide disgust in the assembly, and enthusiastic approval of the sentence of death in the main square of Pavia in two days). More land. Theodelinda, close to the Queen or not, found herself falling back on her old habits of half-listening and assenting to every decision that wasn’t obviously unjust, which in practice meant everything. Well, conserving attention for the important cases was probably a strong tack.

The last case was a feud. Theodelinda couldn’t help herself: she glanced away from the two milites being brought in by the Queen’s bailiffs and looked at Grimoald. He was gazing back at her, something unreadable at this distance but almost certainly furious in his eyes. Her knuckles tightened around her sword. Even if nothing had happened, she had definitely been right to fear an ambush by him last night. — But nothing had happened because she slept all night. Right. She turned her attention back to the field.

The story was the same as every other feud, at least as seen from the abstracting distance of the stands of the royal assembly. His brother and her uncle had a fight, which only suppurated over time; eventually, his brother raised the faida and killed her uncle, after which she killed his brother, and before he could inevitably try to kill her, their Count had dragged them off to Pavia. Their arguments, too, were the inevitable ones: he, that her uncle’s murder was justified and that by killing his brother, she had committed a crime that must be avenged; she, that by killing his brother she had avenged her uncle’s death and served justice.

The Queen seemed to be pondering it, her cilia waving thoughtfully. That opened a window for some speechifying, and several figures towards the front of the stands took the opportunity. Dux Gundiperga — who was probably herself only a year or two away from raising the faida against marchio Rosamunda, and hadn’t she spoken enough already at this session? — took a high-minded approach, suggesting that with a death on each side the equities had been served and that the feud be brought to an end. That was popular, and took the wind a little out of the next set of speeches, which mostly said the same thing with slightly less educated allusion.

Theodelinda, somewhat to her own surprise, found herself standing up. “The uncle’s insults were such that no freeborn man could bear them. He was a coward and a miscreant, and his killing was an act of justice. The feud should be ended in this assembly, today, but the woman should pay recompense for her unjustified reprisal.” That caused a bit of a stir. Even the man down on the field seemed a bit startled that a marchio was publicly taking his side; the woman recovered a bit quicker and glared daggers at her.

The Queen rose. So did everyone else, except for the people down on the field, who knelt. “This feud will be ended today.” She slithered forward from her throne — the wood now wet with nameless secretions — and laid a fleshy palp across each claimant’s shoulder. Theodelinda shook her head, trying to get the renewed sense of abnormality to go away. “Each family has suffered a death. An eye for an eye: justice has been satisfied.” Well, that was that, then. “Will you both swear, before me and your peers, to lay the faida to rest, to uphold the peace, and to embrace again as friends?”

They were not going to be friends. But this was a demand they couldn’t really refuse, before the Queen and assembly. “I swear,” the woman said, and then the man said “I swear”, and the assembly shouted its assent. They embraced, stiffly, and kissed cheeks.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

AT THE FEAST to celebrate the successful conclusion of the court, Theodelinda was again seated at the high end of the hall, near the Queen. She should have been delighted, and was, a little. But the itchy feeling of wrongness wouldn’t go away. Marchio Agilulf, from out west, was seated next to her and talking to her, quite flatteringly, about the Queen’s evident regard for her abilities. If he wanted to side with her she should be glad for the ally; but in practice she had to keep forcing herself to reply with courtesy, rather than simply searching up and down the table for whatever it was that was gnawing at her.

At the head of the table, the kitchen staff brought in a whole roast pig for the Queen to eat. Her forelimbs, black-clawed and bladed with white bone, stabbed down into it, then dragged it across the table towards one of her gaping maws. Theodelinda stared, fascinated. The Queen, discussing poetry with comes Carloman to her left, seemed almost not to notice, merely raising her voice a little as the pig went in and the sounds of tearing flesh and splintering bone began. A dozen long, whiplike tongues lashed out of another mouth and began to methodically lick her outer limbs clean.

“Marchio Theodelinda?” prompted Agilulf.

Theodelinda started. “I’m sorry. I was just… watching the Queen.”

Agilulf smiled. “She is elegant, isn’t she.”

“Yes,” agreed Theodelinda, but her head buzzed like it was full of bees.

Agilulf seemed to misunderstand what Theodelinda had been paying attention to, and tried to bring the conversation around to literature. She was not entirely comfortable with this. Once she’d started moving in Pavian circles, she’d worked at getting herself an education, but so far only to about the level needed to read a Psalter. The only other book she owned — or had read end-to-end — was the Life of Eligius, a solid, undemanding work, but by the same token hardly one to burnish one’s literary reputation. Agilulf had read it too, thankfully, and she was able to keep up with things for a little while. Still, it was a relief when someone interrupted.

“Theodelinda?” That should be marchio Theodelinda, actually, but as she turned in her seat she understood: it was one of Grimoald’s men. She didn’t recall his name. “Quite the speech at the assembly, there. Wrong on the merits, of course, as the Queen recognized.”

“The Queen went with the assembly. That’s not the same as saying she disagreed with me,” Theodelinda said calmly.

“But in this case, it is. What would you know about the honour of a freeborn man?”

“More than, you, apparently,” she replied, still calm, and swung hard with her knife. He was ready for it, of course, and rather than burying it to the hilt in his chest, it just lightly cut his forearm where he deflected it. She kicked her chair at him as she stood — he dodged that too — and slid into a fighting stance, knife in hand. He had his dagger out too, and there was a pause as they sized each other up and the others along the table turned to watch.

“Lowborn peasant scum,” he hissed, apparently trying to provoke her into making an injudicious move again.

“Idiot lickspittle,” she retorted. “You know you’re here to die, right? You can’t beat me, and when I kill you Grimoald will have the law on his side when he raises the faida. You’re just —”

He went in, snarling. Grimoald had sent an idiot. He was fast but she was quick as well, and taller and stronger, and was able to block and force him back with her superior reach. Another pause, and then Theodelinda suddenly rushed forward. He blocked again, but she laid into him with her empty fist and landed the blow, and his guard faltered for a moment as he staggered back and then it was all over. Theodelinda kept hammering and he went down on his ass and she kicked his blade out of his hand and then stepped, hard, on his chest.

“There,” she said, as he glared with undiluted loathing up at her. “I don’t give a rat’s ass about you. So you get to live, you worthless shit. Go crawling back to your master and tell him to come face me himself, next time.” She stepped off of him and turned back to the table.

An odd, repetitive moist popping came from the head of the table, and it wasn’t until the others around her joined in that she realized what it was. Agilulf was cheerfully praising her on her skill and clemency, but Theodelinda was only half-listening, trying to figure out why she hadn’t recognized the sound of the Queen’s applause.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

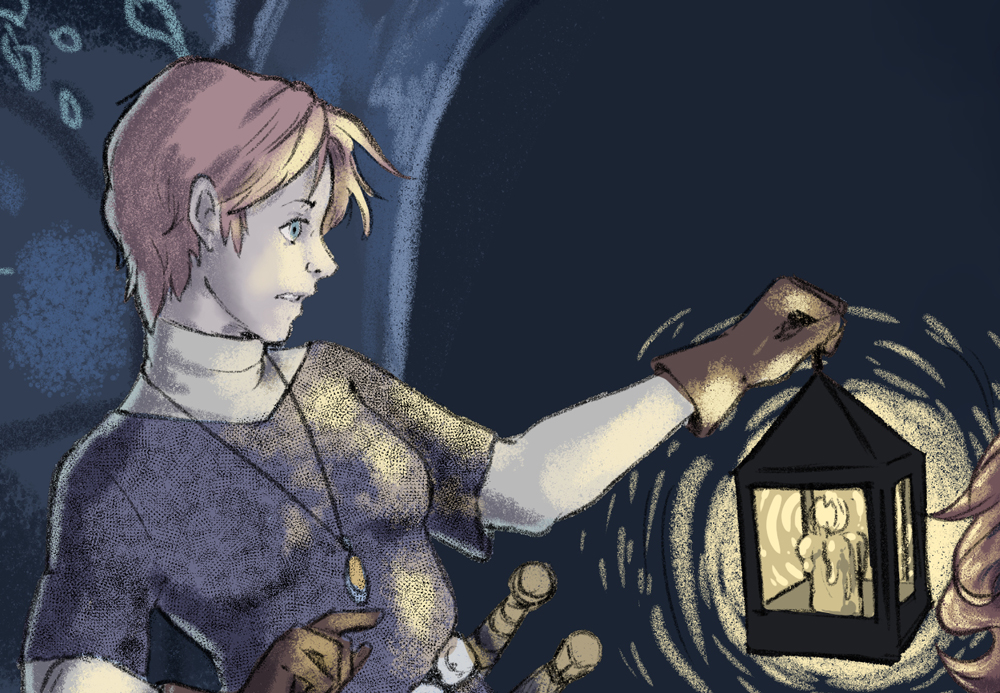

ANSA CAME AGAIN in the middle of the night, although of course it wasn’t “again” and Theodelinda wasn’t sure where the name had come from. “Would you like a lantern?” Ansa asked, holding one up. It was unlit.

“Don’t you need it?” asked Theodelinda.

“No,” said Ansa, with a smirk, and gestured to her brow. It was studded with a constellation of glittering black secondary eyes.

“Right, then,” agreed Theodelinda, uneasily, and started to follow her. Ansa moved confidently into the inky blackness of the city’s streets, and Theodelinda was stumbling and blind in moments. She felt her way clumsily back to her house and lit the lantern off the firepit’s embers. Ansa had followed her back and was waiting, again, outside the door. Her smile was, if anything, even more wickedly amused than before.

Theodelinda mastered her irritation by remembering that the Queen liked her magnanimity, and liked Ansa, and then spent a moment trying to remember when she’d learned that. Ansa was already setting off into the night again, and Theodelinda hurried to follow. Ansa led her through the city without hesitation or interruption, and soon they were at the small side door to the palace that Theodelinda had never seen before. Ansa unlocked it with her key, and they went inside.

Theodelinda followed her through the dark, empty passages of the palace, the sensation of deja vu increasing with every step. When they arrived at the private reception hall, it became almost overwhelming. The Queen was again lounging on her chair, her gorgeous flesh and bone and claw and horn tightly filling the room.

“Thank you, Ansa,” said the Queen, again-ish. “You may stay if you like.”

“I always do,” purred Ansa.

Theodelinda’s head was pounding. She stared at the Queen, the unreality and the wrongness and the familiarity of the situation all swirling into a confused mess. She was sweating. She somehow couldn’t make herself move. She felt like she was in a fever dream.

“Marchio Theodelinda,” said the Queen. “Have you considered my offer?”

“What offer?” Theodelinda managed to rasp.

“The one I made to you last night,” said the Queen. “To serve me as my palatina, rewarded not in land or in titles but in my favour, and in the gifts I can bestow upon you.” Several limbs gestured smoothly to Ansa. Theodelinda looked at the servant girl, who winked and licked her lips: quite a production, with at least four tongues slipping out and tangling erotically with each other as she did so.

“I— I don’t understand,” stammered Theodelinda.

“I know,” said the Queen. “But that too can be changed. UNDERSTAND.”

The world snapped into alignment around Theodelinda. The sense of deja vu was replaced by the practical remembrance that she had, indeed, been here last night; the unreality faded into the ordinary feeling of being present in the world.

That just made the horror worse.

The Queen filled her vision. Throbbing and thrashing, shifting and squirming, and everywhere terribly alive, She was the most horrible thing Theodelinda had ever seen. And so, so beautiful.

“Oh, God,” she whimpered.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

THEODELINDA woke up, bolt upright, drenched in sweat, gasping for air. It had been so real. The nightmare vision was still swimming before her eyes. She stumbled from her bed, shuddering. She couldn’t stop trembling. She could barely stand. That thing was everywhere, even in her memories of the previous day’s assembly. There was no such thing. There could be no such thing. People would have seen it. Nothing like that could possibly have happened.

As she half-leaned, half-lay across the feasting table in her house’s main hall, her shivering slowly subsided. The first light of dawn leaked in through the windows, and the dream’s terrible potency started to ebb. It was a vision, pretty clearly — she’d never had a dream even approaching its force before. Sent to what end? Warning about her ambition, she thought, a vision of her bowing to a monstrous creature and accepting that corruption into herself for power. Grimoauld, you fucker, you were right. She started to giggle.

By the time Luitprand woke up and came in, she had mostly gotten ahold of herself. “Are you alright?” he asked.

“Yeah,” she said, and straightened her nightclothes. They’d both seen more of each other than that on campaign, but she needed to start getting ready for the day. “Rough night. Bad dreams.”

“About the war?” asked Luitprand, solicitously.

Theodelinda laughed, and laughed, and then reined herself in before it could tear back off into mania. “No. Not even close.”

Luitprand seemed confused, but she didn’t want to talk about it more, and eventually he went off to harangue the cook into an early breakfast. Theodelinda returned to her room for proper clothes. The day after the court was always a royal hunt, the last definite one of the season, and as a margrave of the kingdom she fully intended to be there, killing God’s creation and socializing. Maybe a little more humbly than she might have, before. That had been a hell of a vision.

She got her riding clothes together, pulled them on, and grabbed her good spear: the same one she’d carried to her first meeting with the Queen, two days ago — how was it only two days? But the clothes helped, helped ground her in the world of riding and hunting and polite chitchat with other royal officials. By the time she came back out to find Luitprand and Radelchis already eating at the table, the nightmare was back where it belonged, the realm of things half-forgot by daylight.

Luitprand held her horse. Radelchis carried her saddle. It was a bit of an imposition, but having her milites do this for her was an important part of the show. Somewhere in the hunting party, Theodelinda was certain, there would be a dux who had a comes leading their horse out to the city gates. They set out for the palace cheerfully.

At the palace gates, the hunters were assembling. And the Queen was with them.

The blood thundered in Theodelinda’s ears. Her vision went gray at the edges. The only things in the world were her and the Queen. She was so gorgeous, velvet-black slashed with the red of glowing coals; towering over the merely human figures around Her, Her immensity slipping amongst them on delicate legs, as gracefully as any dancer. Even at this distance she could see the eternal motion of Her surface, and the tiny pale oval of Her face, turning to look at Theodelinda, giving her a smile and a wink —

Theodelinda’s knees buckled. She hit the ground, retching. Chewed-up bread and cheese and bile spattered onto the dirt of the road and she stared at it, hacking and coughing. It was so much easier to look at than the Queen. There were no impossible claims laid to beauty by vomit. She coughed some more, felt the acid sting her nose and palate. She wiped tears and snot from her face.

“— you all right? Theo? Theo!” Radelchis was saying, somewhere very close by.

It wasn’t all right. It was real. That was what the Queen was. That was what She had always been. “You can’t even see Her, can you?” she asked, her voice wobbly with fear and disgust and the next racking bout of vomiting. Less breakfast this time, more bile. She watched it soak into the dust.

“Theo, what’s going on? Do you need a physician? I can run to the palace,” said Luitprand.

A physician wouldn’t help. The problem wasn’t with her, it was with the Queen and with a universe that would let Her exist, unnoticed. She coughed again, spat up some ropy phlegm.

Shoes and a long, plain servant’s dress walked into the top of her vision. There was something wrong in the flexion of the ankles and knees, as they gracefully avoided the puddle of puke in front of her. Theodelinda knew who it had to be before she even raised her head.

“The Queen understands if you do not feel up to hunting today,” said Ansa, too-many-eyed face impassive, in her reciting-a-message tone.

“Get away from me,” said Theodelinda, trying to stand back up.

“She knows that this is a… trying moment for you, and wishes —”

“I said get the fuck away from me!” screamed Theodelinda, and took a swing with her spear. Ansa easily darted out of the way — her grip was still weak and trembling, and in any case she was far too shaken in every other way to concentrate on landing the blow. Radelchis grabbed her — not to try to stop her attacking the girl again, but just to keep her upright. She felt very, very, tired. And why wouldn’t she be? She hadn’t exactly been sleeping nights, lately. She started to laugh, and couldn’t stop.

“You know when I’ll be by,” said Ansa, with her damnable smirk, and turned back to the palace. Theodelinda watched her go. Her dress had been sewn with a neat hole in the back for the thick, firm tail that undulated behind her, and Theodelinda wondered if the person who’d made it had even noticed they were doing that, or just ignored it like everything else around the Queen. She laughed, and laughed, and laughed.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

THEODELINDA awoke in her own bed, with the sun just beginning to set. One of the servants — or, for that matter, maybe Luitprand or Radelchis — had cleaned her face and gotten her undressed to sleep again. She didn’t remember that. She could barely remember the two of them hurrying her home to rest. The memories of the last few nights were vivid, by contrast. She couldn’t get the Queen’s face out of her mind. So much that was horrible, and incomprehensible, about and around Her; but as she stared up at the wood and thatch of the ceiling, she kept thinking of the approving smile on Her face as She offered her the role of palatina. It was the same expression she remembered, on the same face with a different body, from when she was promoted to margrave.

She got up, eventually. She put on her undershirt and leggings, and her heavy boots, and then pulled on her mail and belted her sword to her waist. After a moment’s thought she picked up her helm and shield and slung her spear on her back, too.

She didn’t know what was going to happen tonight. But she wasn’t a courtier, however much she sometimes had to act like one. She was a warrior. Whatever was going to befall her, she would not turn away; she would face it like the woman she was.

Her resolve deflated a little when she came out into the hall and found, instead of Ansa, Luitprand and Radelchis waiting for her. It was still barely dusk, after all.

“Marchio!” said Luitprand, worriedly. “How are you feeling?”

“Why are you dressed like that?” asked Radelchis.

She looked helplessly at the confused faces of her two retainers, her closest comrades. She couldn’t possibly explain. Even if she explained, they couldn’t be made to understand.

Well, maybe that was the way out. “The Queen, as you know, is a grotesque monster, and I have an audience with Her tonight. I may be about to die, and if so I intend to die like a warrior, with my boots on. If it comes to that I am certainly going to kill that smug bitch of a serving-girl first.” Luitprand and Radelchis nodded politely, like she was fumbling her way through a practice attempt at literary speechifying. And that was that.

She ate a little leftover food — she had no trouble keeping it down, now that the existential horror of the Queen was less immediate — and they diced away the evening. Eventually Radelchis, and then Luitprand, went off to bed, leaving Theodelinda on her own. Theodelinda wasn’t sure if that was coincidence or the influence of the Queen, but she had her suspicions. She sat alone, by the dying fire, and picked at the notched wood around the rim of her shield. Finally the knock on the door came.

“What exactly do you think is going to happen to you?” asked Ansa, looking her over. It was harder to think of her as a servant girl, seeing her now; cool, amused, in a plain brown dress that was nevertheless perfectly tailored to her, even the inhuman parts. Theodelinda could imagine it, all of a sudden: a third or fourth child of a landless tenant farmer or unfree labourer, probably even poorer than her own family had been; sent to Pavia to earn her own bread or starve, she somehow caught the eye of the Queen, who changed her, enhanced her, blessed her. That smirk was the expression of someone looked down on, endlessly, without even thinking, by aristocrats of every station, but who knew the score: she was the second most powerful person in the kingdom, and it was only made more delicious by the fact that none of them could see it.

Theodelinda could see it, as of one day ago, and she was going to have to start moving fast if she wanted to keep up. “I don’t know what is going to happen,” she said, as humbly as she could manage. “I was hoping you could tell me, palatina Ansa.”

Ansa raised an eyebrow, an act made rather more spectacular by the tiny black beads widening identically above it. “Maybe you can be taught. You’re surely not expecting to bring a sword to a private audience with the Queen, are you?”

“Is there the slightest chance that I could accomplish any kind of harm to Her with it?”

Ansa’s smile got a tad more genuine. “Ha. No. But really, why the getup?”

“I really don’t know what is coming. But I intend to face it like a woman.”

“You’re not going to die tonight, I can promise you that much.” Ansa handed her the lantern and waited politely for her to finish lighting it before moving off into the city.

“Your… eyes,” Theodelinda said, after they had walked a little ways. Ansa stopped and turned around. “They… that is something the Queen did to you, isn’t it?”

“Oh yes,” agreed Ansa, throatily. She licked her lips with her several tongues, the same eroticized demonstration as the previous night. “The tongues, too. And a number of other changes that I’d have to take the dress off to show you.” She looked Theodelinda up and down, as if seeing her for the first time, and took a step towards her, much too close. “Would you like me to show you?”

Theodelinda backed away nervously. “No. I’m not interested in… that sort of thing.”

“I promise, the Queen has made me well worth your while.” Another lick, and hands resting on wide, soft hips, pulling her dress tight to the front of her torso. “Anyone’s while.”

“No,” said Theodelinda, firmer. “I’m sure you are. I’ve never been interested, with anyone.”

Ansa cocked her head and looked at Theodelinda again. “Well. I’m sure that single-mindedness serves you well on campaign.” She turned and started walking. Theodelinda had to hurry again to keep her in the narrow circle of lantern-light. “Theudoald wasn’t like that, you know. Not in Pavia often enough, but when he was…”

Theodelinda felt a little uncomfortable. “Is that required of you?”

“No. Just very enjoyable.”

“If you like.” They walked on in silence.

Eventually they reached the palace. Ansa unlocked the side door and Theodelinda hesitated on the threshold for a moment. Ansa turned back to look at her and she took a deep breath and stepped inside. The passages were almost familiar, now, and she knew when they were about to reach the reception hall. She stopped there, adjusted her belt and her slung spear and shield, put her helm under one arm. It felt almost like her arrival at the aula so long ago.

“Your grace,” said Ansa from inside, “marchio Theodelinda.” She entered.

The Queen sat in state. Upon Her throne, crowned with gold and glory, She gazed benignly at Her subject. The Queen’s greatness and authority and flesh shone before Her, and around Her. Theodelinda walked to the centre of the room, the centre of a swirl of legs and claws and eyes and power. She had meant to stand, and confront Her as best she could; but in Her full presence, for the first time, really, it was all she could do not to kneel.

“Marchio Theodelinda,” said the Queen. Her voice was quiet. “Do you know why you are here?”

“I— I do,” said Theodelinda. She swallowed. “You brought me here to — remake me.”

The Queen laughed. “If you desire. There is a choice before you.” Theodelinda started. “If you wish, I can close your eyes again, and send you back to Friuli with nothing but fading half-forgot fantasies in your mind. I’m sure you would do well there, as you have done already.”

“Or?” asked Theodelinda.

“Or, if you’d rather not remain in a kingdom ruled by one such as I, exile. You could go over the mountains to Austrasia, or to Neustria, or to the Exarchate. Your skills would serve you well there no less than here. If you’d accept it, I could provide you with some money or other small presents before you left, as well, to see you to safety and a lord’s service again.”

“Or,” said Theodelinda, hoarsely.

The Queen’s face moved closer, as if She were leaning forward. Her muscles — where She had muscles — tensed. Even the incessant tapping of Her outermost claws stopped momentarily.

“Or,” said the Queen, softly. “You could accept My offer. Become My palatina. No money and no lands, although you would keep Friuli and, I imagine, spend a great deal of time there defending My kingdom. No one to know, even, except Myself and Ansa and the few others who know already. But you would have My undying gratitude, and the gifts I could bestow upon you in return…”

Theodelinda swallowed. It sounded very loud to her, in the stillness of the room. She was being tempted with great power, personal, physical, political. That no one would know what a palatinus was meaningless — she’d seen the way Ansa looked at the titled officers of the kingdom, and she knew the reputation Theudoald had earned on the battlefield: with that kind of power and the Queen’s ear, she’d be important quickly. But if she had seen it as a warning about ambition when she’d thought it was a vision, how much worse was it being offered to her in reality?

The thought of forgetting all of this — the awful, monstrous truth that this was, in fact, what was in the world — was darkly appealing. But she couldn’t imagine what she could say, out loud, to justify such cowardice. (And Ansa would laugh at her, forever afterwards, though at least she probably wouldn’t be able to notice.)

Fleeing south, or north over the mountains, would be even worse, really. Beyond the tiny fig leaf of not serving the Queen, now that she knew what She was, she would be leaving behind her lands, her home, her decade of fighting and service to the kingdom. When she looked at it that way, the answer was clear, if not easy.

She’d made the decision for herself three days before, after all.

She knelt, and held out her hands, and the Queen, understanding what was happening, extended a slender, delicate grasper towards her. Theodelinda took it between her own hands: it was cool and dry.

“I swore my true faith and allegiance to You,” said Theodelinda. Letting herself slip into the words of protocol and etiquette made it easier, somehow. “I will not forswear myself now.”

“I would release you, if you asked,” said the Queen.

“I do not ask,” said Theodelinda.

“Then rise, palatina Theodelinda.” Theodelinda rose. “Ansa, leave us for this.” Ansa left. Theodelinda was alone with the Queen. Somehow, that prospect seemed less terrible than it had a minute ago.

“So… now…” said Theodelinda, not quite knowing what to ask.

“Now, my brave and loyal servant, a gift in return. It will require a moment of… intimacy.”

Theodelinda felt obscurely betrayed. “Must it? If there’s another way…?”

The Queen laughed. “Not like that. I know not everyone feels quite the same as Ansa.” As She spoke, a slender spine unfolded itself from Her midsection, stiff and keratinous but thread-fine and needle-sharp. “But there must be a connection, deeper and more pure than simply monarch and subject.” It hovered before Theodelinda’s breast.

Theodelinda took a deep breath and nodded, once.

“BECOME,” said the Queen. The needle darted forward and impaled her, stabbing through her mail and through her flesh and through her self —

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

GRIMOALD was waiting for her a few miles away from Pavia.

It had been a challenge, convincing Luitprand and Radelchis that she should leave, after only a few days in the city and when, missed hunts or not, everything seemed to be going so well for them. She couldn’t tell them — having been sworn to secrecy and all that — that she had gotten the favour of the Queen about as successfully as anyone could have imagined, and rather more besides. Ultimately she’d had to pull out the signed orders the Queen had given her, ordering her “as a new margrave”, to return to her lands to inspect them and strengthen the defences before the next year’s campaign against the Friulians. She’d hoped not to, because it looked, honestly, like a reprimand. But Theodelinda was happy to do it, and no longer had any concern about playing politics or missing things at court. If anything really important happened, the Queen would probably send a messenger Herself to fill her in on it. Theodelinda half-hoped that would happen; she was curious to meet the other palatini beyond Ansa. But she asked Luitprand to write regular letters keeping her up to date on the doings of the court as well, just to keep from raising too many suspicions.

She rode out in her loosest travelling shirt, and no mail. She’d tried to put it on but it had too little give, painfully constraining the new armoured protrusions of her flesh. As it was, even the shirt would probably be getting pretty ragged by the time she reached Friuli. Her boots were worse. Painfully too small, and every time she flexed her talons, she could see the stitches straining. If she didn’t need the stirrups, she’d probably have left the boots off, too. As soon as she could afford it, she’d get new mail, fitted to her new torso, and new stirrups. She’d have to overpay the smith, to make up for all the adjustments they’d have to make without noticing.

At least her helm could stay: it sat high enough to not interfere with the free play of her mandibles. She was glad for that. Flexing her outer jaws felt good, and powerful.

A few miles east of Pavia, the road dipped and turned a little, screened by an old vineyard, and sure enough comes Grimoald was there, along with the man she’d beaten at the feast two days before, and three other retainers. They were blocking the road, not that it mattered: Theodelinda slowed to a stop and put her hand on her pommel the moment she realized who it was.

“You’re a strange one,” said Grimoald. “You come down here, greedy and ambitious, get promoted far above your station, and then skip the royal hunt and hie off east again a day later.”

“I have business in Friuli,” she replied, levelly.

“More important than brown-nosing?” said Grimoald, contemptuously. If she’d still just been a new margrave, one generation up from peasant smallholders and desperately dependent on her military skill and the patronage of the more powerful, it very certainly wouldn’t have been: hence her retainers’ confusion. But she wasn’t just that, anymore. She didn’t even look much like that woman anymore, except to people like Grimoald. She grinned, and her mandibles splayed wide.

“What’s it to you? Shouldn’t you be happy there’s one less person in the way of your stupid, never-successful campaign to replace dux Desiderata?”

Grimoald glared at her, which was funny, because he’d obviously come out here to kill her. “Well, it means no one at court will miss you when you’re dead.” Ah, there it was. Grimoald’s followers started to fan out around her.

She unslung her shield and spear. “Come on then,” she said.

The idiot from the dinner went forward first, of course, so she stabbed at him, he blocked with his shield, and she slammed her shield into his chest with all the force she could muster: rather a lot, now, with strange new muscles in her arm uncoiling, and more than he was apparently expecting, because she knocked him clean off his horse.

She had no time to gloat, though, because even as he was tumbling to the ground his friends were rushing her as well. One of them was nearly behind her already and landed a blow with her sword on the small of her back: it stung like being slapped, but without the deep pain of a real wound, so she hoped her new armour plates had successfully turned the blade.

She spun in her saddle. Everyone else seemed to be moving slowly: the woman who’d struck her blinking, and then drawing back for another blow, Theodelinda’s inhuman fortitude already ignored. Is this what it was like for Theudoald, she wondered. No wonder he was so terrible. She lashed out, lightning-fast, and stabbed the woman through the chest even as her shield-arm blocked the strokes from the remaining two. But the spear was caught, on the woman’s armour or spine or something, and as she toppled, coughing blood, Theodelinda’s too-strong grip on it snapped the haft.

“Goddamnit,” she swore, and threw the butt into the face one of the two still mounted, and leapt from her horse onto the other. She felt her free hand’s claws slide out, and grabbed at his sword, raking the flesh of his hand. He yowled and let go, but had the presence of mind to swing his shield edge-on at her face as he did so: a blow that would probably have at least knocked out a few teeth on an ordinary woman. Theodelinda’s outer jaws caught it and ripped a huge hunk of wood out of the rim. She could practically watch his eyes glassing over as he unsaw it. She laughed (spraying chips of masticated wood) and hit him in the gut with her own shield. They topped together off his horse.

Grimoald was still watching: Theodelinda had been moving too fast for him to realize that his followers had already lost. But he was starting to realize that by the time she stood back up, and started to turn his mount away. It would take him too long to get up to speed. She sprinted after him, with quite a bit of pain in her feet as the instinctual motion of running ripped her shoes to tatters, and dragged him down off his horse.

He hit the ground hard and she was on top of him. Her mandibles wrapped around his head: she could feel his pulse, and his skull felt firm and fragile as an eggshell beneath them.

He wasn’t afraid, you had to give him that. “Peasant,” he said, and spat.

“Palatina,” she said, with her inner jaws, and then with her outer jaws she killed him.

Theodelinda stood and turned around. The woman she’d thrown her broken spear at was drawn and ready, but not coming closer; the man she’d taken the sword from was holding his sword-hand tightly but seemed otherwise unharmed. The idiot from the dinner was still flat on the ground; either she’d injured him worse than she’d thought when he fell off his horse, or he’d had the first good idea in his life and was playing dead. The last woman was definitely dead, motionless with two inches of broken wood jutting from her chest.

“Your lord is dead,” she announced, unnecessarily. “The blood is on his hands. I bear no ill-will to you, or to his heirs.” She sheathed her claws and held out her empty hands. “If they, or you, will be my friends, I will share my bread and salt and be your friend, to death. If not —” She snarled, and spread her mandibles, still dripping gore. “I fear no mortal creature, and no faida.”

They stayed out of her way as she remounted her horse. She left the surviving man his sword, for good faith: she needed to practice with her own sword again anyways. She’d fought five attackers and killed two or three of them, but she’d relied too much on her armour to protect her and wrecked a spear and a pair of boots in the process. Theudoald had been killed by weight of numbers, after all, and if she was younger than he had been she also didn’t have the experience with her new flesh that he had had. She needed to train up with her new body, become the warrior for the Queen she now could be.

She hoped there were brigands on the road to Friuli.

Author’s Note: This story takes place in late eighth-century Italy, in the real-life Lombard capital of Pavia. (The Queen is, um, clearly not Charlemagne, though.) I am deeply indebted to Chris Wickham and his excellent The Inheritance of Rome for my sense of the time and place; this is really in a sense a Weird fanfic of that book. If you enjoyed this story… it tells you nothing because Wickham wrote a fairly dense history. But if you enjoyed this and also enjoy historical nonfiction, absolutely give The Inheritance of Rome a read.